18.26.44 How Juno's Breathtaking Jupiter Images Are Made | |

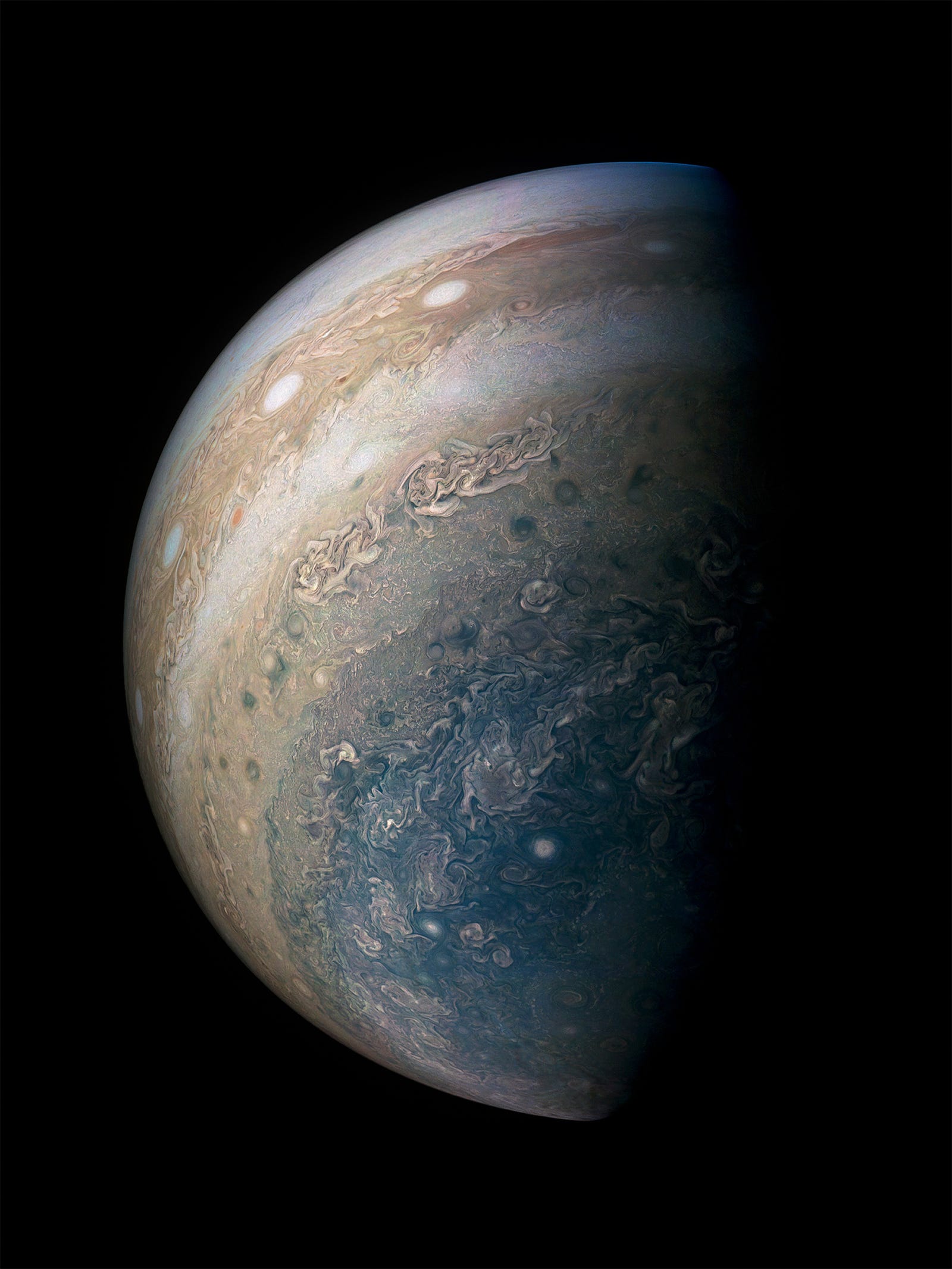

Jupiter’s sandy swirls and blue-hued poles are visible even from Earth. But the Juno spacecraft’s crisp and colorful images begin as warped and dull raw files. The fantastic finished visuals are the result of enthusiastic amateur astronomers, software developers, and artists communicating over message boards. They work together to turn the raw images into accurate art for the space-loving public. On today’s Pretty Scientific, we explore these collaborative efforts. “Image processing is a creative process,” visual artist Seán Doran, who has made a number of the most familiar Jovian images, told Gizmodo. “Every Juno picture is unique and demands a slightly modified approach for each.” The Juno spacecraft is a basketball court-sized, turbine-shaped probe that left Earth in 2011, flew by again in 2013 for a gravitational assist, and arrived at Jupiter in 2016. Its many instruments have demonstrated that Jupiter is far stranger than astronomers ever could have imagined. But one of its instruments, JunoCam, isn’t really intended for scientists. It’s for amateurs like us.

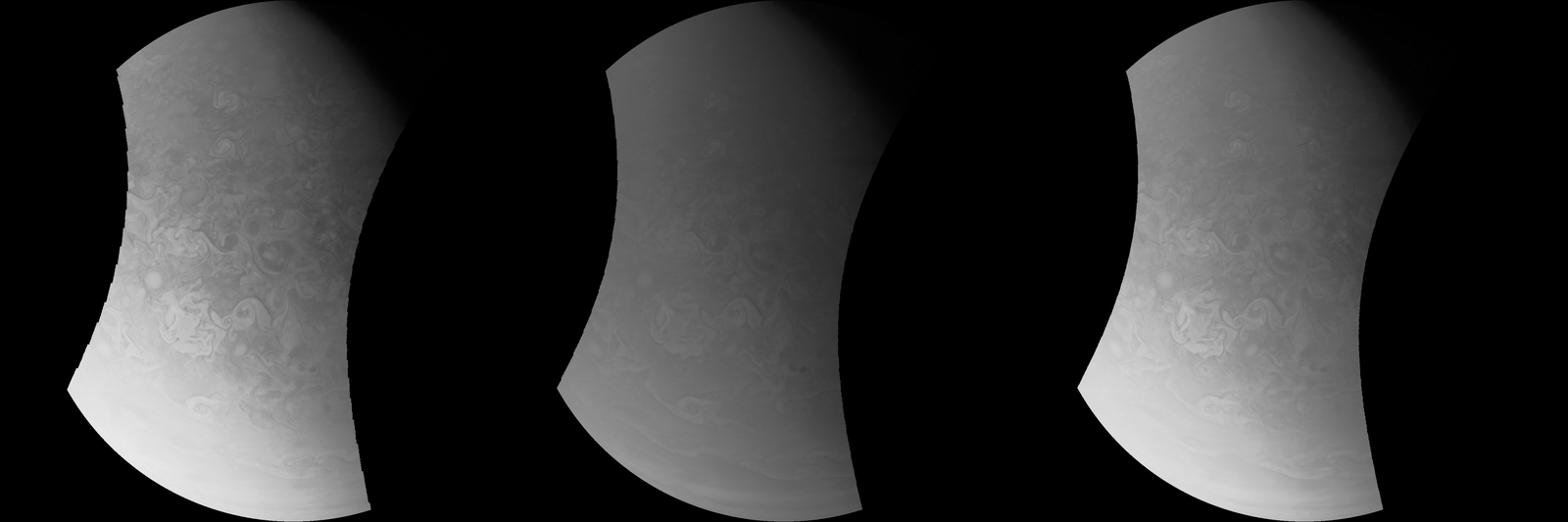

As the spinning Juno probe dives close toward the gas planet, JunoCam begins taking images of locations and features on Jupiter’s surface. These photo ops were once proposed by amateur astronomers and selected through a public vote, but this was suspended after Juno’s eighth Jupiter close-up. The light-detecting charge collection device produces a long and striped black-and-white image. Juno collects some light from the target spots on the planet, rotates some more, switches filters to look at a different color, and collects more light. “It’s something that we do on space images,” Juno Investigator Candy Hansen from the Planetary Science Institute told Gizmodo. “We put a camera on a spinning spacecraft. It’s not exactly a marriage made in heaven.” These snapshots end up on the MissionJuno website, both in the long, striped form and in the individual red, green, and blue hourglass-shaped images extracted from it. X by Counterflix JunoCam’s results are all in the public domain, so theoretically anyone can take the three color filters’ results, pop them into a Photoshop file, and play with them until they’ve got a presentable picture. But photos of a spinning planet from the light detector on a spinning spacecraft often don’t line up perfectly, muddying the planet’s details.

Lots of Jupiter fans are users of the Planetary Society’s Unmanned Spaceflight forum. One ever-present user and German software developer Gerald Eichstädt has written his own software that deals with the mismatches between each color channel and the frame slices caused by the motion. It brightens and dims certain pieces and handles other issues, like dark spots. Once JunoCam’s data becomes available, his software processes the long, raw images and dumps them onto his website and the forum. “It is not quite trivial to solve the task, to process these images in a reasonable time,” Eichstädt told Gizmodo. He practiced first using the images that Juno snapped when it flew by planet Earth for a gravitational assist back in 2013. “It was an interesting challenge.”

Others then take Eichstädt’s images and further process them how they choose. Doran noted that, while incredibly crisp, Eichstädt’s corrections can flatten the image. Doran further processes them to make them more aesthetically pleasing. “[My] images are created in Photoshop where I use multiple layers of non-destructive edits, masks, and filters to arrive at something which is then suitable for re-framing,” Doran said. “The videos are made using a combination of Photoshop, After Effects, and Premiere.” But there’s no monopoly on the image processing and creation. Former NASA employee and DreamWorks animator Betsy Asher Hall blended three separateimages from three separate JunoCam close-ups to create this deep blue view of the planet’s southern storms. And again, all of Eichstädt’s images are public domain (though crediting them as NASA / SwRI / MSSS / Gerald Eichstädt is appropriate, he says). So you can just head in and create your own images.

These amateur astronomers and photo processors aren’t just making pretty pictures, though. Their work is leading to real scientific discoveries. “We’re making use of the data; we’re publishing it, literally,” Scott Bolton, Juno’s Principal Investigator from the Southwest Research Institute, told Gizmodo. “No one knew much about the polar cyclones before,” for example. Of course, pretty pictures are important, too. After all, they’re an easy way to get others excited about studying space and our universe. Read more: https://gizmodo.com/[object%20Object] | |

|

| |

| Total comments: 0 | |