08.35.34 Cameras That Changed Photography Forever Part 1 | |

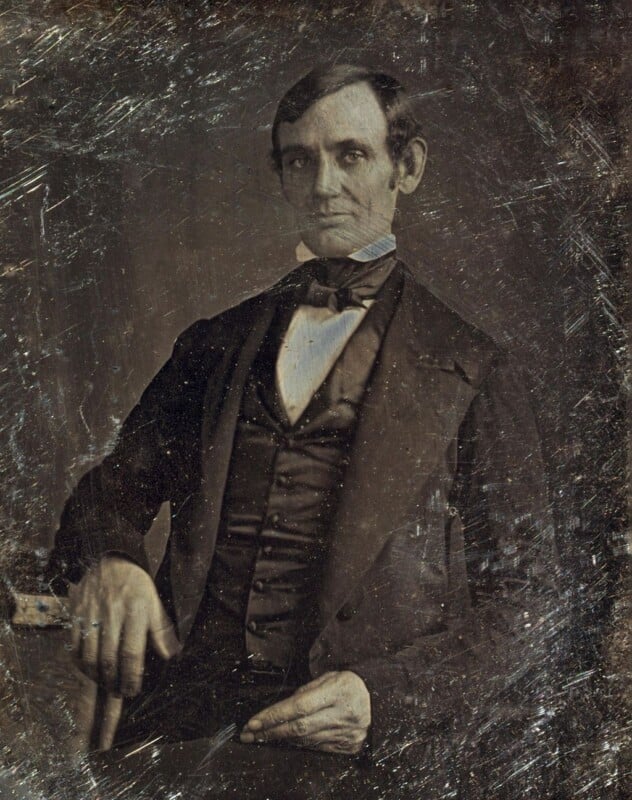

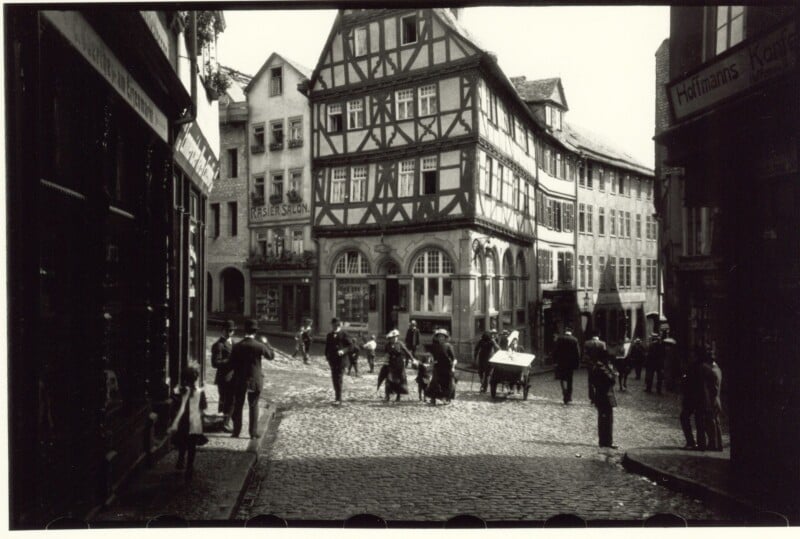

I write about a lot of things here at PetaPixel — reviews, guides, technical articles, opinion pieces — but one of my favorite topics to write about is the history of photography. As an avid user and collector of vintage cameras and lenses, I have passionately absorbed as much knowledge about their history as possible over many years. Like studying world history, there is much value in understanding where we came from and what got to us where we are now. And so I have compiled a list of some of the most important cameras ever made that forever altered the photographic landscape. I know the comments will be full of folks asking why so-and-so wasn’t included or saying they can’t believe I didn’t mention a camera they feel I should have. So, I want to be clear: before cutting it down, my original list contained 69 cameras. Given that this article is over 6,000 words and only has 18 cameras listed, you can do the math and figure out why some had to be omitted. That said, I present some of the most influential, preeminent, history-altering cameras ever made. At a GlanceDaguerreotype (1839)For the purposes of this article, we are going to ignore the camera obscura, as it was not a publicly available photographic camera. Toward the end of his life, Nicéphore Niépce — who used a camera obscura to produce the oldest surviving photograph in 1822 — worked closely with a fellow named Louis Daguerre. After Niépce’s death in 1833, Daguerre inherited his notes and began experimenting with photographing images directly onto a silver-surfaced plate. Perhaps the biggest hurdle at the time was exposure — Niépce’s “View from the Window at Le Gras” required an exposure to the tune of several days. But, in the mid-1830s, Daguerre made a breakthrough. He found that by fuming a polished sheet of silver iodide-coated copper with heated mercury, he could reduce the necessary exposure time to only several minutes. On August 19, 1839, Daguerre and Niépce’s son Isidore presented to the world the first practical photographic process known as the daguerreotype. Unlike Niépce’s approach, which produced a “negative,” the daguerreotype formed a positive image. It was so popular that the French government purchased the rights to the design in exchange for lifetime pensions for Daguerre and Isidore, who were then allowed to release the technology as a gift to the world. Needless to say, the process was a massive success, even being used to take the first verified portrait of a United States President. The daguerreotype would remain the most common commercial process for the next two to three decades until the collodion process replaced it. The Kodak (1888)In 1881, George Eastman, a bank clerk, and Henry Strong launched the Eastman Dry Plate Company in Rochester, New York. Eastman began experimenting with roll film in the mid-1880s and received a patent in 1885. Then he turned his sights to producing a camera that could use roll film. Three years later, he released the camera, known simply as the Kodak. For the first time in history, ordinary people with no real technical skills or knowledge could capture photographs. The Kodak was a straightforward box camera with a fixed-focus 57mm f/9 Rapid Rectilinear lens. It had no viewfinder; on the top were two V-shaped lines, allowing for a rough approximation of the frame. A winder key on the top was used to advance the film, and the rotating barrel shutter was set by pulling a string. After a simple press of a button on the side, the camera would cycle the shutter and take the photo. The shutter itself operated only at a single speed of about 1/25 of a second. The result was circular images 2 1/2 inches in diameter, recorded on a 2 3/4 inch wide roll of film. After finishing the roll, the camera was shipped back to Kodak, along with $10, and the film was developed, transferred to a glass sheet for contact printing, and a print was made. It was then reloaded and sent back to the owner. For those who wanted to develop their own photos, Kodak sold new rolls of film for $2. The Kodak cost $25 ($808 in 2023) and effectively became the world’s first point-and-shoot camera, immediately becoming a massive success and launching a new landscape of amateur photography. “You Press the Button, We Do the Rest” was Kodak’s slogan. The Kodak now exists in the pantheon of photography history as arguably the most important camera ever made. Kodak Brownie (1900)I have previously written about the Kodak Brownie and how it changed privacy rights forever, but this list would be woefully insufficient if it weren’t mentioned again. After the success of the Kodak, Eastman Kodak turned its sights toward expanding the amateur photography market. While the Kodak was a smashing success, it wasn’t particularly cheap, and its rotating shutter was highly prone to developing issues. In 1900, Kodak unveiled the Brownie, cleverly named after the “Brownie” characters in Palmer Cox’s popular children’s books, which made Kodak’s advertising campaign incredibly fruitful. It was a simple leatherette-covered cardboard box fitted with a basic convex-concave meniscus lens, capturing 2 1/4-inch square photos on No. 117 roll film. The camera cost a mere $1 (about $36 in 2023), representing an approximately 97% drop from the cost of the Kodak. The exceedingly affordable price tag — especially for a camera that could be reused — launched Eastman Kodak into the photographic stratosphere. In the first year, Kodak sold a quarter of a million Brownies, and within just five years, that figure was up to over ten million — it was a success far beyond the company’s wildest dreams. After finishing the roll, the camera was shipped back to Kodak, along with $10, and the film was developed, transferred to a glass sheet for contact printing, and a print was made. It was then reloaded and sent back to the owner. For those who wanted to develop their own photos, Kodak sold new rolls of film for $2. The Kodak cost $25 ($808 in 2023) and effectively became the world’s first point-and-shoot camera, immediately becoming a massive success and launching a new landscape of amateur photography. “You Press the Button, We Do the Rest” was Kodak’s slogan. The Kodak now exists in the pantheon of photography history as arguably the most important camera ever made. Kodak Brownie (1900)I have previously written about the Kodak Brownie and how it changed privacy rights forever, but this list would be woefully insufficient if it weren’t mentioned again. After the success of the Kodak, Eastman Kodak turned its sights toward expanding the amateur photography market. While the Kodak was a smashing success, it wasn’t particularly cheap, and its rotating shutter was highly prone to developing issues. In 1900, Kodak unveiled the Brownie, cleverly named after the “Brownie” characters in Palmer Cox’s popular children’s books, which made Kodak’s advertising campaign incredibly fruitful. It was a simple leatherette-covered cardboard box fitted with a basic convex-concave meniscus lens, capturing 2 1/4-inch square photos on No. 117 roll film. The camera cost a mere $1 (about $36 in 2023), representing an approximately 97% drop from the cost of the Kodak. The exceedingly affordable price tag — especially for a camera that could be reused — launched Eastman Kodak into the photographic stratosphere. In the first year, Kodak sold a quarter of a million Brownies, and within just five years, that figure was up to over ten million — it was a success far beyond the company’s wildest dreams. Nevertheless, the camera became a huge success — many of the most iconic photos of all time were taken on Speed Graphics. They remained the go-to option for many photojournalists until the 1950s and 1960s when medium format TLRs and 35mm cameras superseded them. The Speed Graphic continued to be produced — in numerous versions — until 1973. Leica I (1925)In 1913, German engineer Oskar Barnack of Leitz Wetzlar began experimenting with 35mm cinema film for use in a stills camera. Unlike motion picture cameras, which transported the film vertically, Barnack designed a camera to advance the film horizontally, expanding the frame size from 18x24mm to 24x36mm. There was one problem, though: existing 35mm lenses couldn’t project the necessary image circle to cover the larger negative. Barnack turned to Professor Max Berek to develop the first lens designed specifically for the new 24x36mm frame. The result was a 50mm f/3.5 lens with five elements in three groups based on the venerable Cooke triplet. Initially named the Leitz Anastigmat, the lens was later renamed the Elmax (E Leitz + Max Berek). The prototype camera, known as the Ur-Leica, was downright petite, and it was enough to convince Ernst Leitz II to greenlight a pre-production series of cameras for photographers to test in 1923. Despite receiving mixed feedback, Leitz decided to push ahead with production in 1924. Thanks to improvements in optical technology, Berek was able to redesign the lens to be both higher quality and cheaper to produce, resulting in a 50mm f/3.5 four element/three group lens now named the Elmar. Announced at the Leipzig Fair in 1925, the revolutionary camera, known as the Leica I (sometimes referred to as the Model A), permanently put the 35mm format on the map. The compact, ergonomic design was a massive hit. It featured a horizontally-traveling cloth shutter with speeds from 1/20 to 1/500, a film-advance knob and frame counter, a rewind knob, and a small viewfinder for framing. The collapsible 50/3.5 Elmar was non-interchangeable, and the lack of the rangefinder meant it had to be scale-focused. But those shortcomings were of little concern at the time. The Leica I was a watershed moment that would come to define the direction of photography well into the 21st century. Kine Exakta I (1936)In 1936, Ihagee Kamerawerk Steenbergen GmbH of Dresden announced the Kine Exakta. This release represented the world’s first 35mm SLR to see mass production. While the single-lens reflex design was not new, Ihagee put a lot of resources into creating a small 35mm SLR. One obstacle was that ground glass — which would be quite small for a 35mm camera — would make it impossible to focus accurately. So, a Plano-convex magnifying glass with one ground side was used to create a focusing screen in the finder. Additionally, much like many medium format TLRs, a magnifying glass could be popped out to achieve critical focus. Ihagee also had to design fast lenses to amplify the amount of incoming light and enhance visibility in the finder. It turned to Carl Zeiss Jena, who produced a 50mm f/2.8 Tessar, followed by the Biotar 50mm f/2 and Schneider-Kreuznach 50mm f/2 Xenar. The Kine Exakta was hardly the most elegant camera ever built, and its image in the viewfinder was laterally reversed. Still, it was the first camera that truly set the stage for the future dominance of SLR technology. Hasselblad 1600F (1948)Before 1948, Hasselblad’s only cameras, such as the HK7, were aerial cameras produced for the Swedish military during World War II. After the war, Victor Hasselblad turned his attention to the civilian photography market with the goal of creating the “ideal camera.” The resulting camera, introduced in October 1948, was initially known simply as the “Hasselblad Camera,” but it would later be designated the Hasselblad 1600F after its 1/1600 sec maximum shutter speed (“F” was for “focal plane”). It was notable for being the world’s first mainstream medium-format SLR (the first in general was the Pilot 6) and for its design as a system camera — its modular design that enabled users to exchange viewfinders, film backs, and lenses was a novel approach at the time. A decade later, producers of 35mm cameras began to adopt the modular design approach. The 1600F was the beginning of one of the most legendary and respected brands in the history of photography. Nine years after its release, Hasselblad debuted the 500C, the first in a line now known as the “V” system. The modular approach remained in the V system and endured for 75 years until Hasselblad discontinued the H system earlier this year. Even modern digital backs like the CFV II 50C can be used on the original 500C. Hasselblad is also famously the first (and only) company to put a camera on the moon. Leica M3 (1954)By the 1950s, Leica had established itself as the premiere manufacturer of high-quality 35mm cameras and lenses. But all of its models since the Leica I were relatively incremental updates. So, in 1954, Leica released one of the finest cameras ever made: the Leica M3. It used a new bayonet M mount instead of the thread mount in previous Leicas. This made it quicker and easier to unmount a lens and mount a new one, also providing a more secure attachment. Furthermore, Leica Thread Mount lenses could still be used on the M mount with an appropriate adapter. The M3 featured a viewfinder and rangefinder combined into a single window. This was a first for Leica, though other cameras, such as the Contax II, had such a design for years. But the M3’s viewfinder was novel in one significant way — it was extremely bright, with a massive 0.91x magnification. It only contained framelines for 50, 90, and 135mm lenses. However, Leica offered an accessory shoe finder, and some lenses were paired with auxiliary lenses (often referred to as “goggles”) that sit in front of the viewfinder to widen its field of view. Unlike the Barnack Leicas, film loading was significantly more manageable thanks to a hinged flap on the rear of the camera, allowing for easier film positioning when loaded through the bottom. Production of the M3 continued for twelve years until 1966. A massive 220,000 units were sold over that time, and numerous online sources claim it is Leica’s most successful M series model — Leica themselves once told me the M6 was its biggest success, but either way, the M3 is undoubtedly one of Leica’s pinnacle achievements. The M mount is still in use today, making it the oldest mount for which cameras are still produced. Nikon F (1959)I have already written at length about how the Nikon F revolutionized photography, but this is a camera worth a quick recap. As we’ve seen with the Kine Exakta, the Nikon F was hardly the first SLR. It wasn’t even the first SLR with a pentaprism viewfinder — a lens projects an image that is both laterally and vertically reversed, and the reflex mirror projects it re-inverted but still laterally reversed. A pentaprism, however, uses two additional mirror surfaces angled at 90 degrees to laterally flip the image back to normal. Italy’s Rectaflex and Germany’s Zeiss Ikon Contax S, released in 1948 and 1949, respectively, contained the first eye-level pentaprism finders. But it was arguably the Nikon F — the first system camera with a roof pentaprism — that cemented the design as the standard until the emergence and market dominance of mirrorless technology about six decades later. Nippon Kogaku (Nikon) saw an opportunity with the SLR, which had yet to take hold in any substantial way — the rangefinder still reigned supreme. So, under the leadership of Masahiko Fuketa, head engineer at Nippon Kogaku, and with the aesthetic prowess of graphic designer Yusaku Kamekura, the development of the Nikon F began in 1956. The goal was to take the clunky and complex quality of the existing SLRs and turn it into something elegant, polished, simple, and progressive. Several years later, the team locked in the Nikon F’s final design, debuting a camera that boasted a lineup of true advancements: an instant return mirror (first debuted in the Pentax Asahiflex II), interchangeable viewfinders and focusing screens, titanium shutter focal plane shutter, removable back, mirror lockup, an auto-aperture stop-down mechanism for open-aperture focusing and depth of field preview, extraordinarily rugged build quality, and an impressive array of high-quality optics. There was nothing else on the market that combined all these incredible features. For the first time, professional photographers had a 35mm system that could not only meet their existing needs but also open new avenues. Using any focal length — from wide-angle to macro to telephoto — was now feasible, as was the use of zoom lenses. Through-the-lens metering — which was first featured in a prototype Nikon rangefinder known as the SPX — when paired with the Photomic prism finder, was likewise a godsend for many photographers. While the Nikon F didn’t invent many of its most substantial features, it is the camera that managed to fuse all those elements into a single camera body. It became one of the most popular professional cameras ever made and cemented Nikon as one of the world’s most esteemed — and popular — producers of photography gear. Cameras That Changed Photography Forever Part 2

Image credits: Header photo licensed via Depositphotos. Read More: https://petapixel.com/2023/09/30/cameras-that-changed-photography-forever/ Thanks to Petapixel | |

|

| |

| Total comments: 0 | |