09.36.24 Cameras That Changed Photography Forever Part 2 | |

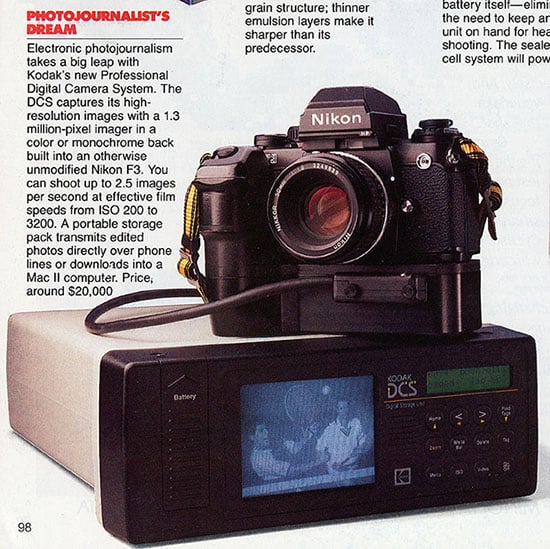

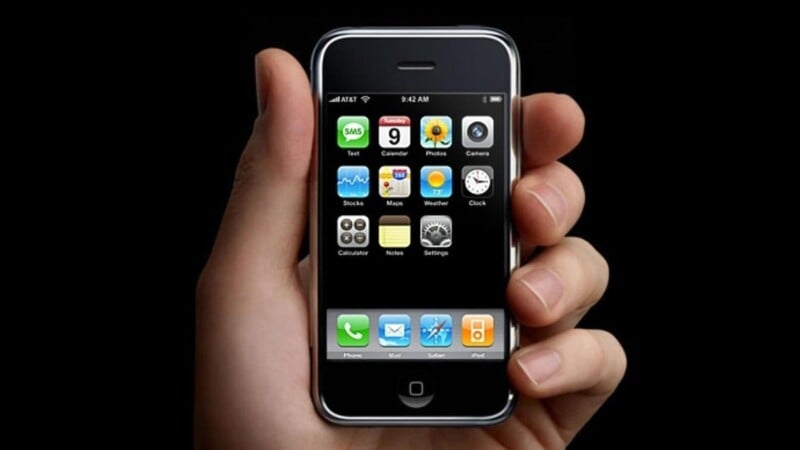

Cameras That Changed Photography Forever Part 1Canon AE-1 (1976)The first Canon SLR, the Canonflex, was introduced in 1959. Before that, Canon was primarily known for its excellent optics — particularly those in Leica Thread Mount — and its rangefinder cameras, such as the Canon IIB, Canon IVSB, Canon VT, and Canon L1 and L3. In 1964, Canon released the Canon FX and Canon FP, which introduced the Canon FL lens mount, moving away from the Canonflex’s R mount. Then, seven years later, in 1971, Canon debuted the Canon F-1 and Canon FTb, which now featured the FD mount. The FD mount was based on the earlier FL mount, and FD mount cameras can use FL lenses in stop-down metering mode. The Canon FD mount was odd — it was a breech-lock mount, which, unlike a typical bayonet mount, would attach to the camera via a rotating ring on the base of the lens. This had the advantage of less potential wear to the lens’s contact surfaces since the lens itself does not rotate against the mount, such as in a bayonet design. The new FD mount also allowed for automatic aperture control along with full-aperture metering, In 1976, Canon released what would become one of the most popular SLRs ever made — the Canon AE-1, which sold an unprecedented 5.7 million bodies. Its success opened up an entirely new market for consumer-focused SLRs, which exploded in popularity in the 1980s. It also holds the historical significance of being the first SLR with a microprocessor. The camera itself isn’t particularly special (aside from its microprocessor), and Canon made the odd choice of opting for shutter priority exposure mode over aperture priority (of course, full manual was available too). But it was a resounding sensation that was inarguably the genesis of Canon’s rise to photographic dominance, which persists to this day. As an interesting piece of trivia, Apple sound designer Jim Reekes recorded the sound of his Canon AE-1 and used it for the screenshot sound on Macintosh computers and later the “shutter” sound on the iPhone’s camera. Kodak DCS 100 (1992)In 1991, the first digital SLR camera hit the commercial market in the form of the Kodak DCS 100. While we now associate the Kodak name with film, the company was one of the early pioneers of digital photography, particularly throughout the 1990s. The DCS 100 body was formed from two primary components: a slightly modified Nikon F3HP body and a customized camera back fitted with a 1.3-megapixel Kodak CCD sensor. The F3HP body was chosen because it was the most popular professional camera at the time of development; the contacts for its motor drive also proved sufficient to synchronize electronic information between the body and back. As the sensor measured 20.5 x 16.4mm, the camera featured a crop factor of about 1.65 diagonally in a 5:4 aspect ratio. Because of this, masks were installed in the viewfinder to indicate the actual capture area of the final image. Interestingly, the DCS 100 was available with either a color or monochrome sensor, and several were manufactured without IR filters. This was a trend that would continue with all future Kodak DCS models. Unsurprising, the first commercial DSLR had several serious drawbacks. Aside from its astronomical $20,000 price tag ($45,000 in 2023), the DCS 100 required an external DSU (Digital Storage Unit) — larger than the camera itself — to be connected to the camera body via a SCSI cable and worn on a shoulder strap. It contained a 3.5” SCSI hard drive with a whopping 200 megabytes of storage, which was suitable for up to 156 uncompressed images or about 600 images using JPEG-compatible compression. There was even an optional keyboard that would allow the user to input captions and metadata. For reasons I probably don’t need to explain, the DCS 100 was highly impractical and never broke into the mainstream. A total of 987 units were sold. But that doesn’t stop it from making the list. Its successor, the DCS 200, debuted the following year with a significantly condensed storage and battery module (now using simple AA batteries) mounted onto the base of the modified Nikon F-801s (aka N8008s) body. Two years later, Kodak followed that up with the DCS 400 series — now built around the Nikon F90 (aka N90) film body — which swapped the 3.5” hard drive with a PCMCIA card slot, and a new 6-megapixel APS-H sensor was offered in the DCS 460. From there, the rest is history. Nikon D1 (1999)The 1990s were marked by the near-monopoly of Kodak in the professional digital camera market. The Nikon D1, officially announced in June 1999, was Nikon’s answer to Kodak’s dominance. While Kodak had released many models in the years prior, they were all built around Nikon and Canon 35mm film bodies. The D1 was the first digital SLR produced entirely in-house. But that wasn’t the only milestone the D1 holds claim to; it’s also the first practical DSLR, both in terms of usability and affordability. Its nearest competitor within the Kodak DCS series cost at least $12,000 ($22,000 in 2023). The D1 debuted at $5,500, less than half the price. It was an extremely capable camera that would ultimately end Kodak’s reign within the professional digital market. Built off the general design and button layout of the Nikon F5, the D1 made for a near-effortless transition from film to digital. But perhaps the most fascinating aspect of the camera was its sensor. In the mid-90s, Nikon formed the ambitious goal of producing its own professional-grade digital camera for only a few thousand dollars. To begin with, no manufacturer would agree to develop the sensor, believing it was unrealistic for such a low price. Eventually, however, Nikon found a manufacturer but experienced trouble with the initial prototypes, which required several watts of power. Determined to create a camera that could be powered by a small (for the time) battery and shoot at high continuous frame rates, Nikon began to develop the circuitry itself. After two years of development, Nikon solved the problem by employing the same circuit technology and image processing used in industrial HD video cameras. Unusually, the sensor even used the NTSC color space standard instead of Adobe RGB or sRGB. Measuring 23.7 x 15.6mm, it was a DX (APS-C) format CCD sensor with a final image output of 2.7 megapixels and a high base ISO of 200. The sensor performed shockingly well throughout its entire sensitivity range (ISO 1600 was the maximum). It was later revealed by Nikon that the sensor possessed 10.8 million photosites with what Nikon called a “quadra filter.” This allowed the sensor to bin (combine) four pixels into one, resulting in excellent high ISO sensitivity and dynamic range. The D1’s sensor was effectively the precursor to Sony’s modern Quad Bayer design. Nikon’s achievements with image circuitry and processing were made all the more impressive considering the 4x higher resolution and incredible five-frame-per-second shooting rate. The release of the Nikon D1 formally inaugurated the ascendency of digital photography as a viable alternative to analog film and entrenched Nikon once again as an industry leader. Canon EOS-1Ds (2002)Contax, one of the unlikeliest candidates, was the first to produce a full-frame digital camera with its Contax N Digital and its Philips 6MP CCD sensor. Announced in late 2000, it was short-lived, as reviews were mixed, and sales were quite low. Contax withdrew it from the market less than a year after its release. And so, it wasn’t until the release of the Canon EOS-1Ds in 2002 that full-frame became a viable reality on the consumer market. At that time, most DSLR sensors were APS-C, yet a vast majority of photographers were using full-frame lenses carried over from the film era. Among other issues, this made wide-angle photography quite tricky, given that very wide-angle lenses at the time were either non-existent, of poor quality, or extremely expensive. The Canon 1Ds featured an 11.1MP — relatively high for the time — CMOS sensor, which made it rather unusual in a time of CCD dominance. Its electronically controlled shutter had a maximum speed of 1/8000th of a second with flash sync at 1/250th. The native ISO ranged from 100 up to a maximum of ISO 1250. A glass pentaprism viewfinder offered a rare 100% coverage, and autoexposure was accomplished via a 21-zone TTL meter that allowed for evaluative, partial, spot, and center-weighted modes. Its molded magnesium body with an integrated vertical grip that housed a large battery was superb, complete with full weather-sealing at every compartment, connector, and button. Perhaps above any other camera, the 1Ds cemented Canon’s stellar reputation among professional photographers in the digital era. Apple iPhone (2007)Primarily known in the mid-2000s as the company that made Macs and iPods, Apple had long toyed with the idea of a touchscreen device that would allow users to interact directly with their fingers. The development of the iPhone officially began in 2005, with its release hidden from the public until its announcement on January 9, 2007. It would be over a year and a half before the first Android smartphone, the HTC Dream, was released, with many dubbing it an “iPhone clone.” The Apple iPhone was one of the most massive successes in modern technological history. Thousands of people reportedly waited outside Apple and AT&T stores days before the launch, and most stores sold out their stock within only a few hours. A mere 74 days after the release, Apple sold its one-millionth iPhone. It instantly became Apple’s most successful product and kickstarted a path that would lead Apple to become America’s most profitable company. They say the best camera is the one you have with you, and that’s what the iPhone was. It didn’t have a great camera — a tiny 2MP sensor was hardly anything to write home about — and it wasn’t even the first smartphone with the ability to take photos. But it was the first to introduce mobile photography on such a massive scale. It would only be five years before the digital camera market peaked, with smartphones driving the enormous decline in camera sales. For better or worse, the Apple iPhone changed the history of photography in ways that only a few other products can claim to have done. Canon 5D Mark II (2008)When discussing cameras that changed photography forever, it would be embarrassing to leave the Canon 5D Mark II off the list. Photography cameras have become decidedly hybridized over the last few years, particularly since the transition to mirrorless across most of the industry. Today, we have numerous cameras in stills-oriented bodies capable of cinema-level video quality — some are even Netflix-approved, like the Panasonic Lumix S1H. Some of these cameras even contain filmmaking features like DCI video, anamorphic support, in-camera LUTs, waveforms, false color, open-gate recording, timecode support, and even external and internal RAW video recording. It’s possible and probable that none of this would exist if not for 2008’s Canon 5D Mark II. While the Nikon D90 was the first stills camera to shoot HD video (720p), the 5D Mark II was the first to record 1080 HD video. With a full-frame 21.1MP sensor, the 16:9 sensor area used to record video was very similar in size to VistaVision 35mm film and larger than traditional Super 35. The large sensor and video specifications opened the gates for amateur and low-budget filmmakers to shoot high-resolution video with shallow depth-of-field to achieve what many considered a “film look.” Prior to the 5D Mark II, low-budget filmmakers were primarily relegated to camcorders with 3CCD Type-1/3” or Type-1/2” sensors — the latter sitting between Super 8 and Super 16 film with a 5.41 crop factor. But with the 5D Mark II, larger format video could be shot in 1080p high definition with easily accessible Canon EF lenses. By today’s standards, the 5D Mark II’s video quality was quite awful. To achieve full-frame 1080 HD video, the camera used line-skipping, recording only every third line, which created significant potential for moiré. The 8-bit 4:2:0 H.264/MPEG-4 compressed files, with a paltry 38 Mbps bitrate, left little room for extensive color grading or other image manipulation, and the sensor’s slow readout speed meant that the rolling shutter was pretty bad. And yet, it marked a new era for amateur and independent videographers and filmmakers and set us on the path toward stills-video hybridization within the camera market. It was even used to shoot an entire episode of the popular television show House and Noah Baumbach’s black-and-white indie hit Frances Ha. Even parts of 2012’s The Avengers were shot with the camera. Nikon D3/D700 (2007/2008)The year is 2007. The first commercially affordable professional camera was launched eight years ago. In the time since, camera technology has seen many changes — some more experimental, like Fujifilm’s SuperCCD sensors, and some profoundly impactful, like the advent of CMOS sensors. Canon dominates the market as the only surviving company to produce full-frame DSLRs. Nikon, which has been Canon’s adversary for decades, is struggling to compete. Enter the Nikon D3 in August of 2007. Successor to the Nikon D2Hs and D2Xs, the D3 was Nikon’s new flagship camera body. Featuring a full-frame sensor — a first for Nikon — the Nikon D3 only sported 12-megapixels of resolution. By contrast, Canon’s flagship DSLR, announced the same month, was the EOS-1Ds Mark III with 21.1MP of resolution. But it didn’t matter because the Nikon D3 blew the competition out of the water with its impeccable dynamic range and high-ISO image quality. While the Canon 1Ds Mark III had a native ISO range of up to 1600 (3200 as an extended option), the Nikon D3’s native range bested that by two whole stops (ISO 6400) and three stops in extended mode (ISO 25,600). The D3 was capable of nine frames per second (11 in DX mode), nearly twice the speed of the Canon’s five frames per second. The D3 also boasted a new Multi-CAM3500FX 51-point autofocus sensor, along with a 1005-pixel AE sensor that was used both for exposure and autofocus tracking via color information. Rounding out some of the D3’s headline features: a new EXPEED processor, a 14-bit ADC (analog-to-digital converter), extremely low 12ms power-up lag, dual CompactFlash slots, a 3.0” 922,000-pixel LCD monitor with live-view, extensive weather and moisture sealing, and a Kevlar/carbon fiber composite shutter rated for up to 300,000 actuations. The following year, Nikon released the D3’s little brother — the Nikon D700. Often heralded as the best DSLR ever made by Nikon, the D700 was a watershed camera that brought high-quality imagery and professional quality to those whose pockets weren’t quite as deep. I started out with a Canon T2i and moved to a used Nikon D700 in 2013. I still have that camera to this day, and it has seen everything from weddings to wildlife to landscape to macro and more. In 2008, three of DXOMark‘s top four highest-scoring cameras were now Nikons. The Nikon D3 and D700 tied for third and fourth place, only behind Nikon’s own 24.5MP D3X and Phase One’s medium format P65 Plus. In 2009, Nikon released the D3s, which improved the D3 and D700’s low-light performance even further. It wasn’t until 2011 that the D3 and D700’s “Sports” score was bested by the Canon EOS 1Dx — though the Nikon D3s remained on top until the Nikon Df’s release in 2013. A legendary camera, the Nikon D3 and D700 have developed something of a cult following, perhaps more than any other digital camera. And I understand why — I still have mine for a reason. Enter the Nikon D3 in August of 2007. Successor to the Nikon D2Hs and D2Xs, the D3 was Nikon’s new flagship camera body. Featuring a full-frame sensor — a first for Nikon — the Nikon D3 only sported 12-megapixels of resolution. By contrast, Canon’s flagship DSLR, announced the same month, was the EOS-1Ds Mark III with 21.1MP of resolution. But it didn’t matter because the Nikon D3 blew the competition out of the water with its impeccable dynamic range and high-ISO image quality. While the Canon 1Ds Mark III had a native ISO range of up to 1600 (3200 as an extended option), the Nikon D3’s native range bested that by two whole stops (ISO 6400) and three stops in extended mode (ISO 25,600). The D3 was capable of nine frames per second (11 in DX mode), nearly twice the speed of the Canon’s five frames per second. The D3 also boasted a new Multi-CAM3500FX 51-point autofocus sensor, along with a 1005-pixel AE sensor that was used both for exposure and autofocus tracking via color information. Rounding out some of the D3’s headline features: a new EXPEED processor, a 14-bit ADC (analog-to-digital converter), extremely low 12ms power-up lag, dual CompactFlash slots, a 3.0” 922,000-pixel LCD monitor with live-view, extensive weather and moisture sealing, and a Kevlar/carbon fiber composite shutter rated for up to 300,000 actuations. The following year, Nikon released the D3’s little brother — the Nikon D700. Often heralded as the best DSLR ever made by Nikon, the D700 was a watershed camera that brought high-quality imagery and professional quality to those whose pockets weren’t quite as deep. I started out with a Canon T2i and moved to a used Nikon D700 in 2013. I still have that camera to this day, and it has seen everything from weddings to wildlife to landscape to macro and more. In 2008, three of DXOMark‘s top four highest-scoring cameras were now Nikons. The Nikon D3 and D700 tied for third and fourth place, only behind Nikon’s own 24.5MP D3X and Phase One’s medium format P65 Plus. In 2009, Nikon released the D3s, which improved the D3 and D700’s low-light performance even further. It wasn’t until 2011 that the D3 and D700’s “Sports” score was bested by the Canon EOS 1Dx — though the Nikon D3s remained on top until the Nikon Df’s release in 2013. A legendary camera, the Nikon D3 and D700 have developed something of a cult following, perhaps more than any other digital camera. And I understand why — I still have mine for a reason. Sony a9 (2017)In 2017, Sony raised the game once again with the release of the Sony a9. Five years earlier, the company had developed the first stacked sensors — the Type-1/3.06 IMX135, Type-1/4 IMX134, and Type-1/4 ISX014, with 13.1, 8.1, and 8.1 megapixels, respectively. These sensors launched Sony’s new Exmor RS line of sensors. In 2008, Sony developed the first BSI (backside illumination) sensor, which moved the metal wiring that sat between the microlens and color filter array and the photodiode substrate to the rear, allowing for enhanced light gathering and faster readout. But there was still room for improvement. Conventional CMOS sensors place the photodiodes and pixel transistors on the same supporting silicon substrate. Stacked sensor designs separate the photodiodes and transistors into two layers, enabling ultra-fast electronic shutter readout. The Sony a9 was the first interchangeable lens camera to feature a stacked sensor. It had a readout speed of 1/160th and could do blackout-free silent shooting at 20 frames per second. This all but eliminated the need for a mechanical shutter in most settings, along with super-fast frame rates and significantly improved autofocus since the camera could perform an enormous number of autofocus calculations per second. Today, stacked sensors have become the de facto standard in flagship cameras. At this point, Nikon, Canon, OM System, and Fujifilm have also adopted stacked sensors in at least one model. And their performance has only progressed since the a9. In fact, the Nikon Z9 — which has the fastest readout of any ILC at 1/270th — was able to do away with a mechanical shutter entirely. Only the Sigma fp and Sigma fp L had previously done that, though they came with severe limitations because of that choice. Last year, the $4,000 full-frame Nikon Z8 debuted without a mechanical shutter. I suspect someday, we will see this across the board. And it wouldn’t be happening if not for the Sony a9. Cameras That Changed Photography Forever Part 1 Image credits: Header photo licensed via Depositphotos. Read More: https://petapixel.com/2023/09/30/cameras-that-changed-photography-forever/ Thanks to Petapixel | |

|

| |

| Total comments: 0 | |